The economy of an operational disruption

It is 7 a.m. on a Tuesday morning in a medium-sized manufacturing company. For example, the leader of the machine group is facing that one machining centre could not be operated during the night shift due to a lack of feedstock. However, the components that could not be produced are now urgently needed in the assembly department in order not to endanger the warranted delivery dates. Using all his experience, skill, unconventional ad-hoc measures and a great deal of commitment, he is able to save the situation using his own initiative. Nevertheless, he is very interested in investigating the operating problem and analyzing its causes.

His research reveals that an unusual design-related change to the bill of material was the cause of the operational disruption. For the group leader, establishing that this exceptional occurrence caused the stoppage brings the matter to a conclusion, particularly in view of the fact that day-to-day operations again demand his full attention.

This example is meant to illustrate what, in our experience, happens in similar situations in almost every company. The employee involved reacts - like many colleagues in his position - pragmatically, but with only a short-term objective.

- Quick, unconventional solution

- Analysis of the cause of the problem

- Decision regarding the further handling of the problem

Astonishingly, many companies tend to tackle problems in the production process by continual improvisation rather than by implementing a defined procedure. However, in these times of decreasing product lifecycles, smaller order quan-tities, increasing variance and high volatility, it is more important than ever for company owners to find an answer to the question of how to set up organizational measures to assure that situations deviating from regular procedures are dealt with in a systematic manner, efficiently and economically.

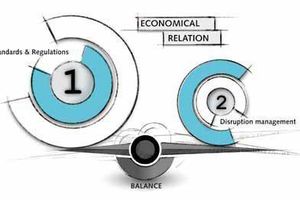

It is a well-known fact that processes are particularly efficient when they are standardized and take place intuitively. Recurring procedures are governed by defined automatisms. These procedures can also be disruptions of known content or of a calculable nature, such as breakage of a machine. The automatisms are derived from standards and rules; they are taught in training courses and involve a high degree of practice. The aim is to achieve the maximum result with comparatively little effort and expenditure. As a consequence, standards and rules form the basis for an efficient process. 80 % of business processes are based on defined procedures.

Unfortunately, the reality of day-to-day company operations is far more complex. Standards and rules require plannable and recurring internal processes, but many disruptive situations are not normally foreseeable in their nature and extent. If one presumes that ideally not more than 5% of our business processes are subject to disruptions, the involved disruptions would still have a negative effect on a not inconsiderable proportion of the entire volume of orders on hand. As a German proverb puts it: “a disruption has many children”. The situation is made more difficult by the fact that a company and its periphery exist in an increasingly dynamic environment.

Our day-to-day operations are subject to constant modification. However, every modification has to be equally regarded as a disturbance of the standardized process. If the existing standards and rules are too tightly defined, every change in procedures is equal to a disruption.

It is surely an indisputable fact that disruptions result in the investment of time and money. However, the actual economic dilemma only becomes truly visible in an extended analysis. From our experience, we know that between 5 and 50 % of the total resultant costs are directly attributable to the disruption. A further 15 to 50 % of the resultant costs are indirect expenses arising in the immediate proximity of the disruption. But so-called consequential costs have by far the greatest impact, accounting for up to 80 % of the total resultant costs. And it is not unusual for these consequential costs to affect every business segment of the company. One decisive factor for the cost development is the point of time that a company reacts to a disruption. A delayed reaction to the disruption results in an increase in resultant costs. This consideration underlines the importance of skilful disruption management.

The foregoing points provoke the question of how we should optimally deal with these issues. The objective must be to achieve an ideal economic relationship between standardized procedures on the one hand and skilful disruption management on the other.

The first necessary step is to analyze and categorize all relevant business processes. The extent to which individual processes are capable of standardization then has to be checked. For suitable processes, appropriate standards and rules then have to be defined. Processes that are unsuitable for standardization also require rules and standards. However, these must be applied moderately, on the one hand rigid enough to provide orientation but on the other hand flexibly interpretable, in order to cope with the complexity and fluidity of today’s requirements. Individually formulated and detailed corporate philosophies provide the solution. These involve rules and standards that authoritatively and connectively state the orientation of the necessary procedure while still affording the involved parties adequate freedom of action.

In addition to the suitable rules and standards, a well-informed and responsible workforce is needed. In this respect, it is necessary to empower the employees in accordance with their decision-making competence, providing them with the qualification and the independent responsibility to disregard the existing standards and rules if required by specific situations, and to act on their own authority in a goal-oriented manner. This demands personal characteristics that were not always encouraged in the past. For many companies it seemed easier to restrict or suppress such independent characteristics, rather than to provide an appropriate framework for such action. Very often, this loss of independent employee responsibility still has negative consequences nowadays.

What is needed is the creation of a corporate culture in which all the employees identify with the company’s operating result and are prepared to participate with their individual commitment. The “department thinking”, which all too often still prevails, has to be broken down and replaced with an sense of responsibility relating to the overall company. It is necessary to fundamentally concentrate the employee’s interest on the superordinate corporate objective. This creates commitment and a willingness to assume personal responsibility on the part of all those involved in the company. To achieve this cultural change, it is not only important to develop a suitable corporate mentality and culture, but also - and especially - to provide the right organizational structure; an organization with an understanding for the declared corporate objective.

Primarily decisive for economically successful disruption management is the manner in which action is taken and the issue is dealt with. A system naturally seeks for stability! Like a gyroscope, a company possesses the greatest possible stability when it is able to turn as quickly as possible, meaning that it can readily handle constant changes in routine procedures and skilled disruption management. If a company is in a position to adapt swiftly and safely to new situations, this will result in efficient disruption management. Successful disruption management thus offers an opportunity to find the most economical alternative to a standardized procedure.

Experienced industrial planners analyze, plan and optimize processes from the conception right up to the implementation. Within this framework, the right handling of disruptions offers great potential. In close coordination and cooperation with customers, business processes can be catalogued after the analysis, and individual standards and rules can be worked out for them. It is also possible to index and train the right employee behaviour, which in turn results in structures for quick monitoring of performance. Reduced to a common denominator, this means that ongoing development of the corporate culture is indispensable.

www.dok-gmbh.de